Review Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone

By Christopher G. Nuttall

One of the problems with coming back to the Harry Potter books so long after they were published is that there is very little left to say. Harry Potter has been analysed backwards and forwards, from the point of view of people who want a good story to detailed studies of the series as a metaphor for racism, sexism and modern-day politics. The characters have alternatively been dressed in leather pants, with their flaws scrubbed clean, or bashed as Death Eaters, with their flaws magnified out of all proportion. Indeed, it is hard to draw the line – sometimes – between canon Potter and fanon Potter.

This is made harder by the films, which effectively take place in an alternate universe, the stage show and Rowling’s own pronouncements. The kid actors did not impress me, when I saw the first movie; indeed, it was a surprise to discover, when I watched The Woman in Black, that Daniel Radcliffe could actually act. People who watch the films and never touch the books, for example, are more inclined to bash Ron Weasley while praising Hermione and admiring Draco. People who read and watch have to accept the differences between the two universes or simply ignore them.

The secret to Harry Potter’s popularity, I think, does not lie in the tired old tropes that Rowling gave new life. There is very little that is actually new in the series. I think it lies in the fact that Harry Potter, like most of Heinlein’s juvenile books, is capable of appealing to both adults and children. There is much to appeal to people of all ages, both simple adventure for the children and deeper meanings for the adults. As one grows older, one’s view of Harry Potter grows older too.

This was true for me, at least. I first read Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, still my favourite Potter book, when I was sixteen. Book three came out when I was seventeen; book four when I was eighteen. And yet, book five left me feeling unsure of everything that had gone before, to the point where I was sure that Harry would man up in the remaining two books. But instead, to my dissatisfaction, he let Dumbledore lead him around by the nose until it was far too late. In a sense, I was caught between the story – which was good in so many ways – and an adult awareness that there were too many unfortunate implications within the text. These days, when I reread, part of me keeps sounding alarm bells. I am no longer a child and I cannot approach the books with a child’s mind.

A child cares nothing for absurd plot holes or fridge horror, an adult notices the unfortunate implications all too well; a child sees the Dursleys as comic relief (in much the same way Matilda’s parents are comic relief); an adult sees the Dursleys as victims of forces they can neither fight nor escape; a child sees Fred and George as jolly and harmless, an adult sees them as perhaps the worst bullies in Hogwarts. The books try too hard to appeal to both adults and children. But these are issues I will discuss when I wrap up this series of essays.

A child cares nothing for absurd plot holes or fridge horror, an adult notices the unfortunate implications all too well; a child sees the Dursleys as comic relief (in much the same way Matilda’s parents are comic relief); an adult sees the Dursleys as victims of forces they can neither fight nor escape; a child sees Fred and George as jolly and harmless, an adult sees them as perhaps the worst bullies in Hogwarts. The books try too hard to appeal to both adults and children. But these are issues I will discuss when I wrap up this series of essays.

It must be noted that I am only talking about the book versions of the story here. I disliked the first two movies and stopped watching after the third went splat.

The plot is known to almost everyone these days, so I will only briefly summarise. Harry Potter, an eleven-year-old boy, is growing up with his aunt, his uncle and his cousin. His relatives are not physically abusive – countless fan-fictions say otherwise – but they are cold and quite distant, while his cousin is an overweight bully. Harry’s life is shattered by the arrival of a letter inviting him to Hogwarts School, whereupon it is revealed that his parents were killed by Lord Voldemort, an evil wizard, and he was left with his relatives for his own safety.

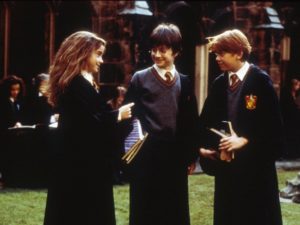

Going to Hogwarts, Harry meets and befriends Ron Weasley and Hermione Granger, while making an enemy out of the snobbish Draco Malfoy. He discovers that his classes are harder than they look, with one class – Potions – dominated by Professor Snape, who hates Harry’s guts, and another run by Professor Quirrell, who wears a turban. Harry discovers that he is a natural sportsman – this is a common trope in boarding school stories – and, eventually, gets dragged into a mystery concerning the Philosopher’s Stone, an item of great power. Harry, convinced that Professor Snape is planning to steal the Stone, plans to save it … only to find out that the real thief is Quirrell, who is possessed by Lord Voldemort. Thankfully, his mother’s protections are alive and well and Quirrell dies when he tries to kill Harry. At the end, Dumbledore reveals that Professor Snape quietly saved Harry’s life … and gives Harry and his friends enough points for their house to win the House Cup. And then he goes back to his relatives.

Going to Hogwarts, Harry meets and befriends Ron Weasley and Hermione Granger, while making an enemy out of the snobbish Draco Malfoy. He discovers that his classes are harder than they look, with one class – Potions – dominated by Professor Snape, who hates Harry’s guts, and another run by Professor Quirrell, who wears a turban. Harry discovers that he is a natural sportsman – this is a common trope in boarding school stories – and, eventually, gets dragged into a mystery concerning the Philosopher’s Stone, an item of great power. Harry, convinced that Professor Snape is planning to steal the Stone, plans to save it … only to find out that the real thief is Quirrell, who is possessed by Lord Voldemort. Thankfully, his mother’s protections are alive and well and Quirrell dies when he tries to kill Harry. At the end, Dumbledore reveals that Professor Snape quietly saved Harry’s life … and gives Harry and his friends enough points for their house to win the House Cup. And then he goes back to his relatives.

It’s fascinating to look back and see just how skilled Rowling was as an author, back in the days when she wasn’t so famous. Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone is a tightly-written book, clearly devised to serve as a stand-alone if the series never took off. It neatly introduces every element of importance, while not leaving too many questions unanswered; it also shows a strong grasp of characterisation that the later filmmakers would ignore in favour of drama or positive discrimination. (In book 3, Ron stands up to Sirius Black; in movie 3, Hermione stands up to him while Ron cowers.)

Much of this lies in Harry and his two friends. Harry himself is brave, having developed a considerable amount of nerve from having to endure his relatives; Ron is brave too, the sort of person Harry would like, with a talent for chess that somehow never pays off later in the series. It takes them longer to befriend Hermione, at least partly because she’s a very domineering – bossy – personality. Rowling captured the problems with being such a person very well – Ron was quite right when he said that Hermione has no friends – and, interestingly, Hermione doesn’t really lose most of her negative character traits. The trio are likeable, in their own way, but also human. Draco gets less development in this book than one might expect; indeed, he’s the stereotypical school bully. He’ll always be a little out of place as the series develops, simply because the real bad guy is Lord Voldemort. How is Draco going to complete?

Much of this lies in Harry and his two friends. Harry himself is brave, having developed a considerable amount of nerve from having to endure his relatives; Ron is brave too, the sort of person Harry would like, with a talent for chess that somehow never pays off later in the series. It takes them longer to befriend Hermione, at least partly because she’s a very domineering – bossy – personality. Rowling captured the problems with being such a person very well – Ron was quite right when he said that Hermione has no friends – and, interestingly, Hermione doesn’t really lose most of her negative character traits. The trio are likeable, in their own way, but also human. Draco gets less development in this book than one might expect; indeed, he’s the stereotypical school bully. He’ll always be a little out of place as the series develops, simply because the real bad guy is Lord Voldemort. How is Draco going to complete?

Other aspects lie in the world Rowling created for her characters. The Wizarding World is colourful enough for a child to love, yet also detailed enough for an adult to pull the pieces together to create a functioning world. (And countless fan fictions have tried.) Hogwarts is both a place of magic and a school that would be very familiar to anyone born before the Second World War. The Houses, the House Cup, the importance of sports (and, less pleasantly, teachers who are not particularly nice) are all part of the standard boarding school tropes. Indeed, compared to some of the boarding schools in fiction, Hogwarts is actually quite tame.

The teachers also fit moulds defined by writers who predated Rowling by decades. Strict teachers like Professor McGonagall (and strict/sadist teachers like Professor Snape) are really updated versions of the original tropes. Headmaster Dumbledore is also a stock character, the kindly old headmaster who refuses to expel the heroes … although, even in this book, it’s clear he’s more of a dodgy character than it seems. Even Quirrell, the traitor, has his origins in older fiction.

The teachers also fit moulds defined by writers who predated Rowling by decades. Strict teachers like Professor McGonagall (and strict/sadist teachers like Professor Snape) are really updated versions of the original tropes. Headmaster Dumbledore is also a stock character, the kindly old headmaster who refuses to expel the heroes … although, even in this book, it’s clear he’s more of a dodgy character than it seems. Even Quirrell, the traitor, has his origins in older fiction.

I loved this book; I still love this book. And yet, as an adult, it has its disturbing moments.

First, it’s all-too-clear why Harry’s relatives resent his presence. He was dumped on them, literally left on their steps. Dumbledore did not even have the courtesy to visit and tell Aunt Petunia what happened to her sister. And, as far as we know, no money changed hands. The Dursleys would have had to shell out a great deal of money, in a hurry, to pay for everything Harry would need. Dudley wasn’t old enough for most of his cast-offs to be of any use (at the time) to Harry. If nothing else, they’d have to invest in a second car seat and a double-seated pushchair. (Believe me, babies are expensive.) Dumbledore treated Harry’s aunt and uncle like servants. In hindsight, it is clear that he wanted to force them to take Harry in, rather than giving them the choice. They might have refused.

Second, Dumbledore is a terrifyingly inept headmaster. It’s clear, in hindsight, that he knew that Professor Quirrell was possessed … and did nothing. He left a potentially world-ending threat alone until it was almost too late. Quirrell tried to kill Harry at least once. What’s to stop Quirrell from poisoning Harry? We know from Book 6 that poison works in Hogwarts (it nearly killed Ron). In a rational world, Dumbledore would have been pensioned off by now, if he wasn’t summarily sacked.

Second, Dumbledore is a terrifyingly inept headmaster. It’s clear, in hindsight, that he knew that Professor Quirrell was possessed … and did nothing. He left a potentially world-ending threat alone until it was almost too late. Quirrell tried to kill Harry at least once. What’s to stop Quirrell from poisoning Harry? We know from Book 6 that poison works in Hogwarts (it nearly killed Ron). In a rational world, Dumbledore would have been pensioned off by now, if he wasn’t summarily sacked.

Indeed, Dumbledore is actually quite cruel. He forces the Dursleys, who have no recourse, to work for him. He deliberately minimises the hatred between Snape and Harry’s father, choosing to frame it as a rivalry akin to Harry-Draco rather than naked four-on-one bullying; he doesn’t think to warn Harry to be respectful to Snape, nor to give Snape an attitude adjustment. It isn’t as if Snape has to maintain his cover. It would have been easy for him to tell Voldemort that he was ordered to suck up to Harry Potter. And, at the end, Dumbledore pointlessly humiliates Slytherin House in front of the entire school. All of a sudden, the problems Dumbledore would encounter later don’t seem quite so unjustified. How many students who weren’t in Slytherin House went off Dumbledore after that?

But then, the Wizarding World as a whole – even in this book – is quite cruel.

Looking back, it’s also easy to see where my frustrations with the books started. I am not, and never have been, an orphan, but if I had access to a whole library of information about my dead parents I’d use it. I’d also learn to use magic to protect myself, as I’d know – as Harry does – that there’s an evil wizard out for my blood. (I might also use the money in my vault to bribe my relatives.) Harry, by contrast, seems not to worry about anything unless it prods him in the nose, which leaves him dangerously ignorant time and time again. As he gets older, this just gets more and more annoying.

Taken on its own, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone is also a complete stand-alone story. All three of the trio – and some of their friends – get a chance to shine, from Ron risking his life to Hermione cracking a riddle to let Harry pass into the final chamber; their victory, however pointless it may seem in the long run, is well deserved. And yet, as the start of a series, it also reads very well. The characters are recognisable people, the school is a fantastic setting and – for a child – it is perfect. Even an adult can admire pieces of it.

Taken on its own, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone is also a complete stand-alone story. All three of the trio – and some of their friends – get a chance to shine, from Ron risking his life to Hermione cracking a riddle to let Harry pass into the final chamber; their victory, however pointless it may seem in the long run, is well deserved. And yet, as the start of a series, it also reads very well. The characters are recognisable people, the school is a fantastic setting and – for a child – it is perfect. Even an adult can admire pieces of it.

I liked it. And so did literally millions of other readers.

Before I go on, I’d like to say that I think what you write here is absolutely on point and I agree with almost all of it. But what I’d like to add is that what problematizes this type of criticism of Harry Potter is the cartoonish nature of the world itself.

For example: Quidditch. The top speed of the Firebolt is given as 130 mph. We may assume that even the slowest Quidditch brooms would manage at least half that speed. Mid-air collisions, crashes with the ground, are all described as fairly common in Quidditch. And the Bludgers are described as made of IRON. What would happen if two kids hit each other — or a Bludger — at a closing speed of 130 mph? To say nothing of +200 mph?

You’d be lucky to get through a match without a fatality. Quidditch is Rollerball on brooms.

So in the context of ALL THAT, is it fair, for example, to characterize Fred and George (or Draco Malfoy) as horrible bullies? Well, by the rules of our world, certainly they are. By the rules of a cartoon world? Harder to say.

Funny I had the same thoughts about the Dursleys yesterday, wizards have a contempt for us non magical even the so called good ones.

That’s an interesting take on Dumbledore and the Dursleys.

Mind you, I’d have Dumbledore provide money to them to care for Harry as well (along with Dumbledore or his agent keeping an eye on how Harry is treated) but I wasn’t thinking about the problems for them to have this baby “dumped on them”.

I wonder if the Dursleys had any access to any of James and Lily’s money. Seems weird that they had a nice amount and it wasn’t used to take care of Baby Harry.

Maybe Dumbledore thought they were well-enough off.

Perhaps.

But I was more concerned that Dumbledore wasn’t “keeping an eye on things” to make sure Baby Harry was treated nicely.

As it was, Harry might have become a muggles hater just like Voldemort. 🙁

Oh, I remember reading the ending of the first book where Harry is talking about Dursleys don’t know that Harry isn’t allowed to use magic in their home.

Personally, if I was Harry, I might have ignored that rule. After all, nobody was watching to make sure the Dursleys treated me OK, so they might not be watching now to see if I use magic in their home.

Oh, I might not have “done anything to them”, but letting them know that I could would be a different matter. 😈

Good discussion – made me think.

I didn’t like HP until the series was finished – and I had watched the movies (with only mild enjoyment) up to HBP (the movies are generally superficial and incoherent). I had also read the Wikipedia summaries of all the books in order to chat with my primary-school-age daughter, who was mad about HP.

Then, because the HBP movie was so incomprehensible, I read that book and went straight on to Deathly Hallows. I was bowled-over by DH – which I regard as a superb, deep, book. And with DH as ‘key’, I went back and re-read all the earlier books, with great enjoyment.

Now, I would regard the HP series as among the best works of Eng Lang fiction; certainly by a living author – but the key to it all is in the last book, where the Christian sub-structure comes to the surface so beautifully and movingly. It is Deathly Hallows which raises Harry Potter to greatness.

My appreciation of what was going-on in DH was greatly helped by a Jerram Barrs video – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MxySk24J_bs – and a book by John Granger – The Deathly Hallows Lectures (2008)