Which Magic School Is For You: Roke

Long before Hogwarts became everyone’s favorite magic school, there was the first fantastical magic school: Roke

I say first fantastical magic school specifically. There were magic schools before that, but they were old ideas like the School of the Night, where the Devil teaches black magic and one out of every ten students will be tithed to Hell. (We will have a guest post on this kind of magic school later in the month.)

How many of you ever wished you could attend Roke? I bet many readers don’t even know what Roke is.

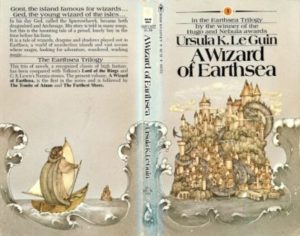

Once upon a time, in the long-ago dream time of the 1970s and 80s, there were three fantasy series everyone read: Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, C. S. Lewis’s Narnia Chronicles, and Ursula LeGuin’s Earthsea Trilogy. Everyone who read fantasy had read all three, and they were considered equally great.

I remember the day, some years ago now, when I realized that while Narnia and Lord of the Rings had made the grade, Earthsea had been basically forgotten. Many modern fantasy fans had never heard of the books. They didn’t even know that LeGuin had invented one of their favorite concepts: the magic school.

But Ursula Leguin’s magic school in Wizard of Earth Sea was the first time a fantasy writer thought “Gee, we see so many wizards in stories. Who trains them? Where do they go to school?”

And what she gave us was Roke.

In some ways, Roke is still my favorite of all magical schools. I would probably rather actually attend Hogwarts (or Roanoke). For one thing, Roke is only for men. But there is a enchanted quality about Roke, a magic of the place itself, that stands out to me, even now.

The magical school of Roke is on the Island of Roke. This island is protected by the Master Windkey and his students, so many people cannot even find the island.

On the island is the town of Thwll, ….and the school. But they don’t make it easy to find the school. If asked, the townsfolk reply, “The wise don’t need to ask, and the foolish ask in vain.” Or, perhaps, “You cannot always find the Warder where he is, but sometimes you can find him where he is not.”

Roke is that kind of school.

If you should be so lucky as to find the school—a simple wooden door in a great building on the square—you will discover that even if you walk through the door, you ware still standing on the street outside. To actually enter, you must be granted entrance by the Master Doorkeeper. He does not let people in unless they give him their true name.

Don’t know your true name? Then alas, you are not qualified for Roke. But if you do, wonders await!

Studio Ghibli made a movie about Earthsea–but Roke was not in it.

When you have stepped in, the door behind you is no longer a simple wooden one, but made of a solid piece of ivory…it was made from a single tooth of one of the great dragons. The dragons of Earthsea are powerful and wondrously wise and quite unlike dragons in other places.

Good dragons—ones who are not merely greedy and violent—are a dime a dozen now, but once upon a time, the only good dragons in fantasy literature lived in Earthsea.

Once you were allowed inside, the place was even more magical—a place built both of stone and of magic far stronger than stone. If you are lucky you will have a moment when you realized that the singing of the birds and the rushing of the water and the wind in the sky are all speaking to you, all words, and that you, yourself, are also a word.

For that is the kind of understanding you will need if you are truly to become a Namer.

Within are the Great Hall, open courts with grass and gardens, roofed halls, the Room of Shelves where books of lore and runic tomes are kept, a refectory with a Long Table for eating at which, they say, there is always room for another, no matter how many sit down, Hearth Hall for festivals, and dormitories under the eaves of the towers. There is the Imminent Grove watched over by the Master Patterner, and, at the far north of the island, Isolation Tower, where one studies the art of Naming.

The students are a rowdy lot, hailing from across the Archipelago, of varying skin colors and nationalities. The older ones, the sorcerers, dressed in gray cloaks, clasped at the throat with silver. But only the graduates, the mages, carried a staff.

They learn sailing in the bay and how to call up magewinds. All their boats have eyes painted upon them. The students play pranks upon the town, or study in silence in the Tower, where the Master Namer tells them:

“Magic consists of the true naming of a thing. Many a mage of great power has spent his whole life to find out the name of one single thing—one single lost or hidden name. And still the lists are not finished. Nor will they, till worlds’ end. Listen, and you will see why. In the world under the sun, and in the other world that has no sun, there is much that has nothing to do with men and men’s speech, and there are powers beyond our power. But magic, true magic, is worked only by those beings that speak the Hardic tongue of Earthsea, or the Old Speech from which it grew.

“That is the language dragons speak, and the language Segoy spoke who made the islands of the world, and the language of our lays and songs, spells, enchantments, and invocations. Its words lie hidden and changed among our Hardic words. We call the foam on the waves sukien: that word is made from two words of the Old Speech, suk, feather, and inien, the sea. But you cannot charm the foam calling it sukien; you must use its own true name in the Old Speech, which is essa. Any witch knows a few of these words in the Old Speech, and a mage knows many. But there are many more, and some of have been lost over the ages, and some have been hidden, and some are only known to the dragons and to the Old Powers of Earth, and some are known to no living creature; and no man could learn them all. For there is no end to that language.”

Roke is run by the Nine Masters and their leader, the Archmage of Roke. The nine masters are the teachers from whom students learn magecraft. Those nine masters are:

Master Doorkeeper—who guards the gates.

Master Windkey—who teaches the arts of wind and weather, steering boats and stilling waves.

Master Hand—who teaches sleight of hand and the lesser arts of Changing.

Master Herbal—who teaches the ways and properties of things that grow, as well as healing.

Master Changer—who teaches illusions and the true Spells of Shaping.

Master Summoner—who teaches true magic, the summoning of heat and light and forces that men perceive as weight, form, and color as well as the wisdom to know when not to do such things.

Master Namer—who writes down the true names of things that his students must learn before the words fade at midnight.

Master Chanter—from whom the future sorcerers and mages learned the Deeds of heroes and the Lays of wizards, beginning with the oldest of all songs, The Creation of Ea.

Master Patterner—I never did figure out exactly what the Patterner did. Apparently, he teaches something so deep and mysterious that no mages speak of it.

The ancient old dragons are the best part of Earthsea, though this is a young one.

The leader of the school itself is the Archmage, the most powerful of all mages in the world. The Archmage is chosen by the Nine Masters, and it is he who sees to it that Roke is protected.

Roke is a quieter place than the majority of magic schools we visit, somberer and closer to the heart of magic. From it come wizards, mages, some who go home to work wonders for their people; others of whom venture forth to find missing names or, if they are very lucky, speak with dragons. A few even speak with dragons…and live.

No one who goes into Roke comes out unchanged.

“they say, there is always room for another” Wasn’t it, always just enough seats? Not quite the same, Memory may have failed me.

I had the book open and was quoting/paraphrasing, but it is possible that I paraphrased more than I intended to.

Master Patterner – grammarian at large. Where others teach and study words and phrases, he studies the grammar of the world, to understand the inner essence. It appears to be a very zen-like understanding and acceptance. “Listen to the leaves,” indeed.

I think that if I lived in a world where magic was available, I would choose the world of Heinlein’s Magic, Inc. where it is taught at any good university.

Recently a confluence of many sources is leading me to think of philosophy and theology more in terms of that which in stories of magic you here refer to by noting that no student leaves Roke unchanged. Now that I write this I recall also that Chesterton notes this quality (or rather something deeper than quality) of life in his Orthodoxy. The notion though is that one can only really understand a thing from inside it and by entering into the life of it; and one cannot trade in its weights and measures but by participation. And so for the same reason a magic that is a mere science in modern terms (“I pay 20 mana to cast fireball”) seems as vacuous as the theological objections of atheists (generally speaking). The devil at least, with his black magic, requires horrid anti-sacraments. But the devil’s modernism is more like that in Earthsea, when the names are lost. The last anti-sacrament is to forget the notion of sacrament; a torture so unwholesome we lose sensation of pain – and of pleasure.

Apologies for rambling; I look forward to seeing future installments of this series.