Article by S.Dorman

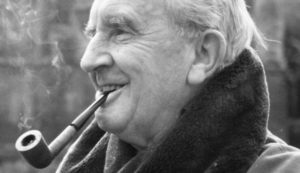

Author and journalist John Garth taught a course at Signum University on Tolkien’s War-time experience and its influence on language and creativity. J.R.R. Tolkien seems always to have been a lover of high diction, in communion with his love of philology and making languages, but Mr. Garth points out that Tolkien’s tonal range was varied and brightened in deepening his art, and that, as in later works, he varied styles within his great stories to reveal and harmonize social and cultural notes. But Mr. Garth says, also, that his use of high diction underscored hopeful values and timeless themes. And, as Tolkien himself put it (in my paraphrase), here was a freeing from “trivial associations,” fully resonant with the remembrance of good and evil. (From his Beowulf essay in The Monsters and the Critics.) Language, he discovers as the great war begins for him, depends on conveyance of legends.

Author and journalist John Garth taught a course at Signum University on Tolkien’s War-time experience and its influence on language and creativity. J.R.R. Tolkien seems always to have been a lover of high diction, in communion with his love of philology and making languages, but Mr. Garth points out that Tolkien’s tonal range was varied and brightened in deepening his art, and that, as in later works, he varied styles within his great stories to reveal and harmonize social and cultural notes. But Mr. Garth says, also, that his use of high diction underscored hopeful values and timeless themes. And, as Tolkien himself put it (in my paraphrase), here was a freeing from “trivial associations,” fully resonant with the remembrance of good and evil. (From his Beowulf essay in The Monsters and the Critics.) Language, he discovers as the great war begins for him, depends on conveyance of legends.

In a 1954 letter by Hugh Brogan fault was found with Tolkien’s use of high diction. There’s a lot in Tolkien’s response (not sent) to this critique, but I caught on what cannot be underrated in sub-creativity: Tolkien responded to Brogan’s criticism that he saw no point in neglecting ancient language forms anymore than in making his weaponry like that of modern warfare. This reminded me of the incongruity I first felt on seeing some medieval or renaissance paintings depicting biblical scenes wholly without the setting in which they occurred. These scenes were shown as renaissance contemporaneous, and in the current fashion of that day. No doubt these were loved in their place and time if projecting weirdly today. Translation can make a disjunction in creative vision a bit like seeing the lead actors of El Cid wearing ducktails and Brill-cream when everything else looks period—the armor, sweeping scenes of battle and jousting and columns of Moors marching. You’re not so much thrown out of the vision as thrown into another, an alternate universe of color and taste.

And Brogan says elsewhere that Tolkien was “temperamentally incapable” of our dictum “make it new.” Oddly, he did not seem to think that Tolkien was making it new, making the heroic quest new so that readers might see it, become immersed in it, and understand it once again.

Language in world-building is as important as landscape, as the scent or look of the time—or structures and clothing and hairstyles—all conveying imaginative meaning. Writers want to bring the imagination of the reader into the story with everything available.

I’m fairly sure Mr. Brogan did not mean that Tolkien should use the pop language of the day, the 1950s or 60s, the “yeah yeah yeah.” But whatever it was Hugh Brogan would want to be used, would he have considered the sort of artistry involved, and how it would look 30 years down the road? Or two centuries. If Tolkien wanted to have King Elessar say “yea,” still, it would be no good having him say “yea yea yea.” Is it artistry in making that builds the world, gives it its language, clothing, structure, gives life? Ayuh. (Mainer for “yes.”)

Can writer or reader “hear” what kind of English would better suit the world-making? Given our creative use of alternate worlds and universes, it would not be impossible today to make a landscape with buildings and clothing, hairstyles, etc. all having the look of Tolkien’s Middle-earth, and it may even be possible to use the language of our own day in such a world, but it would be a great and peculiar artistry if the language managed to make it real for the (celebrated) reader’s imagination. Wouldn’t such language rather conjure suits and ties, jeans and backward baseball caps, tattoos and spike heels… without apt artistry?

A world must be made of sound—as well as landscape, heroic and violent culture, and whatever sort of rings and letters (runes) are shown as a part of its decoration and life. Could you make a story in which the wood thrush sang like a chicken (b-buck-buck-buck), or a chicken growled like a bear? If it works for the imagination, that would be good artistry indeed.

John Garth, who taught the course on Tolkien’s Wars at Signum University where I began thinking about this piece, liked the analogy of renaissance biblical art being out of phase with its subject. In a forum, he shared the idea that current styles may disguise current cultural ideas, disturbing the feel of novelistic narrative time and place. Are we trying to imagine a medieval world? It must look and sound medieval, avoid tonal superficiality—through artistry—and the cultural trends of today.

Tolkien’s use of high diction in speeches may feel overdone to some. Because of the difficulty in expressing something better suited to a particular moment, or dramatic presentation, I don’t think it out of place. I wonder if great and stirring speeches ever “sound” as good in any prose books as they would in person on the given occasion? It must be a living context that makes them fitting, moving. An atmosphere either solemn or celebratory that would not suppress embodied, encompassing, and emotional creaturely experience.

And here one example—which comes flitting to mind—is when one of the gospel writers reports Jesus saying that the stones would cry out in praise of him if the crowd kept silent. This is the message with a power to transcend any language, material, fashion, or age.

Probably the closest in the medium of imaginary experience that we can come is to see a stage production or feel the imaginary vicarious uplifting after immersion in a period film. And, according to Crystal Downing in her essay in Christianity Today, Dorothy L. Sayers used the slang and everyday language of the day in her 1941 radio production for a cycle of plays. It was damned by many Christians who found it blasphemous. In our day, those praising God might be wearing t-shirts and ties, tights, flannels or jeans, be tattooed, or texting—but transported all the same.

© S. Dorman

Dorman has lived in Maine and studied its ways for thirty-five years. She is the author of several speculative fictions, including The God’s Cycle, Five Points Akropolis, and Fantastic Travelogue. Maine Metaphor: The Green and Blue House is her first book in the series of Maine creative nonfiction, put out by Wipf & Stock. Review copies may be requested at the publisher’s website.