Article by S. Dorman

Tevildo Prince of Cats was the first imaginative incarnation of Sauron the Dark Lord, whose power was destroyed in the unmaking of his Ring in the Third Age of Middle-earth. As many know, the process of writing is drafting and redrafting, a sort of making and remaking. An early incarnation of one character told of his learning the tongues of animals, tongues of various elves, of monsters and the early incarnation of orcs, called goblins. And it told of this character’s frustrations in such learning. He even learned the speech of beetles. Yet most of all, learning the languages of men vexed that character. Here we have just a bit of Tolkien himself and how he was inspired under turmoil of WWI to work hard at his invented languages. According to John Garth—teaching Tolkien and the Great War—war provided necessary pressure to do good and continuing work.

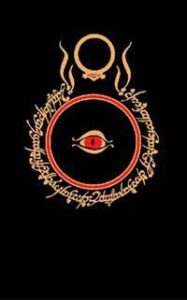

The subject of Sauron’s appearance came up in the Signum University course on Tolkien and the World Wars, which brought in Paul Fussell’s discussion of “gross dichotomies” in enemy characterizations during time of war. On my first reading of LotR I lived in imaginative expectation of Frodo’s eventual meeting with the Dark Lord. As fellow Inkling Warren Lewis suggested in his journal after listening to Tolkien read harrowing scenes, the presence of the Dark Lord is strong in imagination, making one anticipate Frodo’s encounter with his actual form. Because of the elaborate sub-creation of this world I was so involved I felt sure climax must involve a face-to-face with Sauron. One may keep wondering how this is going to be handled by the author. I saw discussion on a weblog some time ago about the non-showing in person of Middle-earth’s Dark Lord. One commenter was emphatically grateful that Tolkien had not displayed evil in an imaginatively personal form.

It was partly an extra-textual expectation: a scarcely recognized lookout for how authors did things. I was lightning-struck and then completely wrapped up in how this was (not) accomplished. Hugh Brogan, in “Tolkien’s Great War,” called it one of the story’s best literary devices. There was a thrill as I listened to Rob Inglis’ dramatic reading—hearing and standing imaginatively beside the wizard as this great battle turned and Gandalf cried the quest had been achieved.

Probably scholars and critics have discussed this “device” often. And I have considered it over the years, realizing every time how effective it was, but also coming up with an extra-textual reason for it. This may sound off —on account of his handling of Shelob, Ungoliant, Melkor and Melko; Glaurung! and others. However, these characters are handled somewhat remotely or in snippets, not always—but largely—from a distance. Maybe it was Tolkien’s own interior innocence stopping him here. For whatever reasons, whether extra-textual, narrative or story-bound, its effectiveness would be bound up in distance.

I asked this question in a Mythgard forum for the course, and one student answered in confirmation of course lecturer John Garth’s explication that Frodo was encumbered with the Dark Lord’s presence throughout the quest to unmake the ring. The imagination of both reader and character work brilliantly in this handling.

It is a non-showing, powerful and suggestive, but more effective than any face-to-face with a person Tolkien might have provided. Perhaps I could call it showing suggestively: Spiritual combat rather than a face-to-face. The face-to-face meeting for Frodo and readers is nonexistent.

In my experience of Tolkien’s evil ones, which is not scholarly, nor deep-reading, I feel them in my imagination at some remove. However, while reading and listening to John Garth, author of Tolkien and the Great War, I had a much greater sense of the spiritual dilemma of the inhabitants of Middle-earth. And through spiritual descriptions of the evil influence of Melko in The Book of Lost Tales, and in the later reimagined Melkor, and in then the “nameless one” (Sauron) in his various textual incarnations, I wondered—is there to be no true crushing imaginary face-to-face? We do have face-to-face confrontations between Hurin and Melkor in The Silmarillion, and maybe one or two others, and Sauron with other names, earlier, as well, but they seem removed, remote, just as the telling of The Silmarillion itself seems remote.

Obviously Tolkien was face to face with his evil characters in imagining them. And perhaps he continued to be for the rest of his life as he reworked them. That is, he did not become disenchanted after they were created. I disagree with his friend Christopher Wiseman who wrote to Tolkien that finished work is vanity, that, once created, characters are essentially dead. Wiseman’s idea? That characters are solely alive in being worked out on paper. Mr. Garth compared the continuing process to the ongoing living music of the Ainur in Tolkien’s sub-creating world. Also, I wonder if Christopher Wiseman was perhaps thinking on paper, wanting to map out his own thoughts, prod his friend, and be alive himself, while doing so, during the war. And many of Tolkien’s characters seemed never-finished in his recreation of them as he kept retroactively refitting them for continuity. But to readers such as myself they seem living, and (maybe) not finished, either. Yet I feel something true in Wiseman’s words on this. A sub-creator so absorbed in the process feels “disappeared” into it. (Anyone else looking sees them at their easel or desk, the reverse invisibility of a would-be Ring wielder.)

But I think that Tolkien did give us a person-to-person, face-to-face with Sauron. That he gave us the imaginative close-up without remoteness or more impersonal narrative later used by elvish framers of tales. Mr. Garth describes this particular incarnational dark lord’s face-to-face as “astonishing[ly] grotesque, vain, capricious, and cruel.” And his name, in The Book of Lost Tales, was Tevildo Prince of Cats. Maybe Tevildo is the one Frodo would have seen face-to-face had he been taken before Sauron.

Artists don’t need temporary charismatic or political power, or the might granted to Hitler in his later life. To express evil, they need only be able to paint postcards, extend vision on pieces of paper. Controlled and precise, Tolkien’s artistic acuity rejected display of the “ruddy little …” as pathetic. This is what Tolkien called Hitler in real life: “ruddy little ignoramus.” Perhaps “The Ring-bearer has fulfilled his Quest,” would not have been such a powerful thrilling moment for readers if the thing using the ring’s power were shown as a Tevildo or a Gollum. One might almost say Tevildo was the creature Frodo saw face-to-face, day in and day out, on his guided tour of Mordor: and that it was ignorant little Tevildo who bit off his finger and fell into the fire, consumed.

From the textual history students were given, we learned that he wasn’t the nameless after all. He had many names. Sauron Deceiver, Gorthaur the Cruel, Thû, Abominable, Thauron, the Enemy, the Dark Lord of Mordor, the Eye of Barad-dûr, Lord of the Rings. —This? This paltry being deceiver of all Endor? (Though some were not deceived but still had to fight.)

Tolkien’s narratives shape-shifted—in a continuous state of recreation, refitting, rethinking. We know CS Lewis relied on images, “pictures,” and tying them together with narrative. But from Lewis and Tolkien we also learn to research things needed to make a story picturesque, deep, live. This course showed me detailed unity in Tolkien’s work over time, bringing aid in imagining a face-to-face between Frodo and the Dark Lord. I’m not a reader of poetry and so don’t know Milton’s intellectual Satan.

Otherwise, and younger, I might have immersed my imagination in his charismatic Satan. Because for some devilish reason it then interested me to know about the devil, to see Sauron face-to-face. But Tevildo is not the great Miltonian figure, as I understand from Paradise Lost summaries. Sauron’s shape-shifting days were over after the downfall of Numenor (where he achieved intellectual power, and the uncorrupted man form)—before loosing much in the destruction he planned.

If power were stripped from Sauron, power which can only be on loan to him, what’s left is Tevildo the kitchen master, bullying, paltry and proud. As Sauron (née Tevildo) he could only have been a bully using that spirit in bodily form face-to-face to harm Frodo after retrieving the ring in Mordor. I don’t think, given these pathetic qualities, he would have said to himself, “Now where was I?” —and forgotten about Frodo. On Gollum he used intimidation with a purpose, but the dark lord’s pathetic selfishness would have taken vengeance on someone who is not craven. And Frodo, I’m imagining, would have stood up to it without the ring, no matter the frightful form standing before him.

Perhaps this is wrong.

Venom in a small creature can kill. The venom was in the ring on Sauron’s hand for his use until Isildur cut off and carried it away. Frodo, after his experience of oppression in Morgul Vale, might not have loved his life enough to care. Seriously, imagine Frodo sticking his tongue out: If he were undeceived. Power, cloaking the paltriness of Sauron, goes with the ring. When the ring goes, power is gone, and we see the surprising little thing. What, this!? —this paltry being deceived (almost) the whole world?

© S. Dorman

© S. Dorman

This essay is part of a collection on creativity. There are three essay books, each of which has the phrase “free will” in its title.

- Dorman is author of Fantastic Travelogue: Mark Twain and C.S. Lewis Talk Things over in The Hereafter, a science fiction spun off her Master’s thesis in humanities from California State University Dominguez Hills. (The thesis revolved around the Christian foundation of the humanities.)

Visit S. Dorman’s Author Page.

Thanks for this! A lot to savor and ponder! (And interesting to aspire to compare with Tolstoy’s treatment of Napoleon, as I finally get through War and Peace thanks to Alexander Scourby’s fine reading aloud of the Maude translation.) I wonder if there are good Milton audios which would facilitate your enjoyment of Paradise Lost and Paradise Regained? (Slow reader, as undergraduate I read them aloud to try to get through them in good time – standing around our men’s dorm lobby on at least one occasion – when a blind friend hearing the distant thunder as he approached, thought at first some street-preacher must have gotten in somehow.)