How best to go about telling a Bildungsroman for the son of Arathorn II, for a youth who would become the Good King Elessar? Achieving qualities Tolkien so carefully evoked in his great cosmology and Lord of the Rings stories, the landscape, map, and texts of Middle-earth provide answers, addressing formal and structural concerns through the narrative device of the journey. So the best way would be to consult the map of Third Age Endor made by J.R.R.T.—as Dr. Tom Shippey says Tolkien did when he needed inspiration. The landscape of Middle-earth would suggest everything needed to tell the story of a youth unsure of his identity, in need of knowledge and an opportunity to serve, in search of training, adventures, and understanding of the various peoples he would encounter. All his life in the hidden realm he has known not Men, but elves.

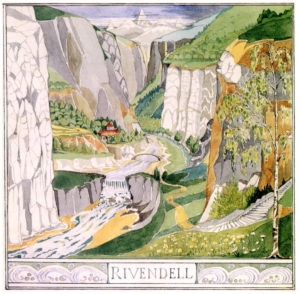

Movie Rivendell

Estel, meaning Hope, was the name given him by the elf-master for his fostering in Rivendell, where he came with his mother, Gilraen, following his father’s death. The storywriter would want to preserve the mystery of Imladris and so would give but what was suggestive, as the place where his journey begins. One would want to preserve the mysterious elusive and allusive beauty of the elves by showing them, too, as little as possible. What would that leave of Estel’s childhood to show? Perhaps his coming of age in wayfaring through the wildlands, town-lands, and other realms of Third Age Middle-earth. Tolkien’s wandering theme, for Estel’s further and grown-up life as Strider (a Ranger, a Watcher), would provide the writer’s basis to invoke a desire in the youth to travel and train for such a life.

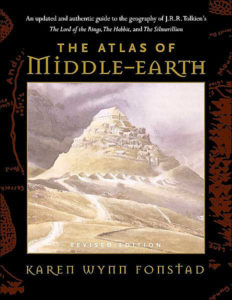

Photocopying, cutting, and pasting together a large map of the various regions, as set forth in Karen Wynn Fonstad’s admirable The Atlas of Middle-earth, might give an aspirant the tactile and intellectual familiarity with materials necessary to begin the project. After this, in search of the unfolding story, he or she could hang the great cobbled-together map on the wall above a workspace where fan fiction is to be set down. The writer might be something like the youthful Estel looking over fragmentary maps he had copied from the archives of Imladris, in hopes of plotting out his adventure.

Photocopying, cutting, and pasting together a large map of the various regions, as set forth in Karen Wynn Fonstad’s admirable The Atlas of Middle-earth, might give an aspirant the tactile and intellectual familiarity with materials necessary to begin the project. After this, in search of the unfolding story, he or she could hang the great cobbled-together map on the wall above a workspace where fan fiction is to be set down. The writer might be something like the youthful Estel looking over fragmentary maps he had copied from the archives of Imladris, in hopes of plotting out his adventure.

Land features are significant in Tolkien’s works. Such features are often inhabited or imbued with history, with personification (the Powers who are making and remaking land forms), with Peoples (such as dwarves linked with caverns). Another land “feature” is cataclysm: kingdoms and civilizations disappear under the sea when their lands are overcome with destruction. The motif of the wave repeated throughout, in stories and in conversation, would reference impermanence and judgment—as well as history. For when lands fell under the wave, the First and Second Ages fell with them. Estel himself would muse on such changes and histories, but what has such cataclysm, such judgment and impermanence, to do with a young one starting out who can’t even confirm whom he is? Even before leaving Rivendell he would perhaps know more of Arda than of himself.

Tolkien’s sketch of Rivendell

Let’s look at the map. Is it unreasonable to believe Estel had never been far north of Rivendell? No matter how much the writer of Estel Wandering might desire to explore Angmar and the Grey Mountains, he or she would well forgo, for in The Fellowship of the Ring Strider has revealed to his four hobbit charges that the Ettenmoors remained unexplored by him. The teller of this tale would instead have him convince his mother and Elrond that he is ready to begin training himself to become a Ranger by traveling south and west through The Angle and South Downs. After leaving the magic realm of his only known home, he on his great steed, would see what can be found of old remnants: of the Stoors (mostly moldering stonewalls, mounds, and cellar holes), of ruinous kingdoms of Third Age Westernesse (nobler remnants showing high realms and peoples sundering—Arthedain, Rhudaur, Cardolan). From these old sites he would track up the Greenway toward Bree. Here, in this story we are now calling Estel Wandering, he might first meet Men and perhaps stay in an inn, there being afforded the opportunity to learn how men and women get on, and to socialize at last with these his own kind.

While still a child at Imladris, perched on a limb outside this last homely house, perhaps he had espied a hobbit—one Mr. Bilbo Baggins (on that one’s own journey There and Back Again). It was then Estel first desired to see hobbits in their native country. If the writer is following the sound of Tolkien’s map-checking footfalls, it would be back to the map again in which, hoping to find their land, Estel might see the River Baranduin (the Brandywine) and decide to follow it into the Shire.

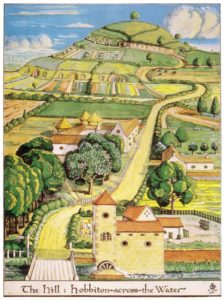

Tolkien’s glimpse of The Hill in Hobbiton

In the Shire he would encounter the most wholesome kind of life he would find on his travels anywhere. The land of the hobbits, with their villages, farmland, community ways, conventionality and apparent security, might at first prove daunting to him, the outlandish other-lander, one of the big folk. But, on being befriended by the most unconventional of its members, he would discover something valuable to inspire him for the rest of his days in troubled Third Age Middle-earth. The peculiar household of Mr. Bilbo Baggins might also provide for both talk and instances of book-learning and map reading; and even map-making.

Since this work is based on that of Tolkien’s, place names would evoke their peculiar suggestiveness along its title character’s route. But in Dunland is an opportunity to explore such suggestiveness, while at the same time furthering Estel’s quest. From what little is given of the history and inhabitants of Dunland in Tolkien’s work, it is evident that suggestiveness and inspiration must here help the writer of our tale once again. We look at the names Dunland and Dunharrow, the latter a mysterious place in a further land, and that land not so poor as Dunland, and we think: is there any connection for us in the coupling of these two names? We know that Dunlendings are a poor and unfriendly sort of folk. The land is not particularly well endowed. Maybe they even keep slaves as a sort of comfort in their poverty. Theirs is a history of having lived better, of having enemies to the south, the Forgoil, or Strawheads, as they call the Rohirrim. Estel might discover that there is some sort of mystery here, relating to a possible further destination.

Back to Professor Tolkien’s map. Where to go next? The storywriter decides it’s time to move on to Rohan, land of the horse-people. He or she needs a bit of adventure here, and knowledge of history in this land provokes the reminder that once upon a time the Woses were hunted in the Riddermark. What better way to show off Estel’s natural indignation at mistreatment of all the speaking creatures of Eru than to introduce the mystery of both folk with some careless cruelty of the horse-people—when he discovers that the latter’s courtesy does not extend to more primal men? What better way to have him experience this land, see some of its features, meet some of its folk, and bring them into judgment by the West-marshal, than through Estel’s indignant interference in the sport of the locals?

There are many ways in which a questing youth might find trials in this land. They need not be severe, but they must be interesting. The land, and its history found in the chronology and other appendices in the third volume of The Lord of the Rings, will suggest what comes next: the challenge to bring a Wild-man to sup, the charge to bring gold to King Fengel? Harmless enough. Yet these adventures might lead to the ultimate exploration of Estel’s now primary target: Dunharrow and the Paths of the Dead, bane of his curiosity. At Dunharrow, the storyteller might take the hint, given by Aragorn in the third volume of LOTR, that only a dire but necessary risk would lead him to pass upon that haunted way: Therefore he must first have had some experience with it earlier in life.

Minas Tireth — Movie version

After that of course it’s on to Minas Tirith. For a few years to follow, it may appear that this has been his goal all along, for the young man might take up his studies afresh here in the City, and, with it as a base, could, if the storyteller’s imagination were to allow, go out to receive training from the Rangers of North Ithilien.

An intriguing episode with maps might occur during the course of his studies in the City when Estel encounters various versions of a single mapped territory. I would suggest venturing verbal descriptions of Tolkien’s own versions such as have been discovered through Christopher Tolkien’s explorations in drafts of his father’s earlier works. With a bit of narrative magic the teller of Estel’s tale would encourage in readers the idea of divergent texts in a single archive, simulating historical discontinuity; and with it the mystery of place as it was in the human imagination when all the world was little-known outside the local community.

As a matter of course, when we look up at the wall map our eye is drawn to Mordor. The writer might want to think of a way to bring Estel into the dread land. Putting him among the Rangers of North Ithilien may open the way for this. This will have to be a scene of power corresponding to the catastrophic power that is meant by Mordor, the land of total degradation and destruction, mapped out for us both verbally and pictorially in the products of Tolkien’s imagination. Landforms such as Udûn, the great Caldera, the volcano of Mount Doom, slag heaps, ash deserts, and the Ephel Dúath embody the catastrophe.

As a matter of course, when we look up at the wall map our eye is drawn to Mordor. The writer might want to think of a way to bring Estel into the dread land. Putting him among the Rangers of North Ithilien may open the way for this. This will have to be a scene of power corresponding to the catastrophic power that is meant by Mordor, the land of total degradation and destruction, mapped out for us both verbally and pictorially in the products of Tolkien’s imagination. Landforms such as Udûn, the great Caldera, the volcano of Mount Doom, slag heaps, ash deserts, and the Ephel Dúath embody the catastrophe.

As with the elves, it should be written in a way to maintain mystery, while at the same time expressive of atmosphere and the engines of evil. The would-be writer’s expression of the scene would not figure anywhere except in the personal experience of Estel, and would resonate through his coming life and hope. There should be suffering. There should be confusion and consternation. There should be the Bildungsroman trial to youth, its fledgling understanding of its identity. And there should be coming away, from that awful land, in some means sobered and matured.

After that and in dénouement, Estel would again look at the map and, seeing Belegaer on the margins of the earth, consider how he might acquire passage, and so round out his journey exploring in some part the realm of Ulmo. A circle would be created, bringing the traveling Estel back once again into the vicinity of the Shire. Then you’d want to make a good ending, suggestive of homecoming among elves; again with elusiveness and mystery. The young man Estel, born of Wandering Star (Gilraen), might return in time to meet Arwen, Royal Maiden, coming home from a distant realm. But this meeting would be for another story. The story of a grown man, using extended mapping.

A map can be an invocation, an inspiration; a tool or instrument for imagining a land for the nourishment dreams. All this you might consider, all this you have to work with in drafting your story and leafing it out.

Conversely, if a writer decided to write the paper on how such a thing might be done, he or she might write the story first, see how it was managed, and then report on it.

This is what I have done here.

*

Works Consulted:

Fonstad, Karen Wynn. The Atlas of Middle-earth, Revised Edition. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1991.

Shippey, T. A. The Road to Middle-earth. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1983.

Tolkien, J. R. R. The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien. Ed. Humphrey Carpenter. Boston: Houghton Mifflin

Company, 1981.

—. The Lord of the Rings. New York: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1994.

—. The Silmarillion. Ed. Christopher Tolkien. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company,

1977

Dorman writes biblical fan fiction, speculative fiction set in an alternate universe. She also publishes Mary Shelly fan fiction, Gott’im’s Monster 1808, set in the western mountains of Maine.

.